The Decidability Tradeoff

What is Undecidability

Like Icarus flying too close to the sun it seems that every mathematical system will eventually be drawn towards the black hole of undecidability. Decidability basically means there is an algorithm to answer a question. Adding Numbers is decidable but finding the shortest path is not. In general I have noticed a pattern in all systems of rules. The system starts off simple. Then, as more use cases pile up, more rules and properties are added until suddenly, the system is undecidable. What happend here? I will start with a few examples

Typing Systems for Programming Languages

I first encountered this problem in the type system of programming languages, or basically

an algorithm that says 5 is an integer or [1,2,3] is a list of integers. You may think this problem is easy, and indeed the way I have just phrased it is decidable by Algorithm W. A type system is very useful,

but people have encountered corner cases, such as depenedent types or linear types, and they

try to extend the type system. For example, if you are trying to figure out the type of

C's printf, you might realise that the type of the second

argument depends on the type of the first argument.

printf("%f %s", 1.2, "hello")

If you want to encode this information into the type system, then you have just discovered dependent types, where types depend on values. The problem of finding out if a dependently typed program is valid is actually undecidable (as a subset of the halting problem). One you say you want this, you have stepped out of the safety of decidable typing and you might now need to prove to the compiler using a formal proof that a program typchecks, such as in languages such as Idris. A good documentation of this problem is on the website typing is hard.

In my view, the ideal type system of a programming language should be decidable. I don't want to have to write a proof that my progam is valid. The best type system for this is Hindley-Milner which is about as far as you can creep before you plumet off the cliff of undeciability.

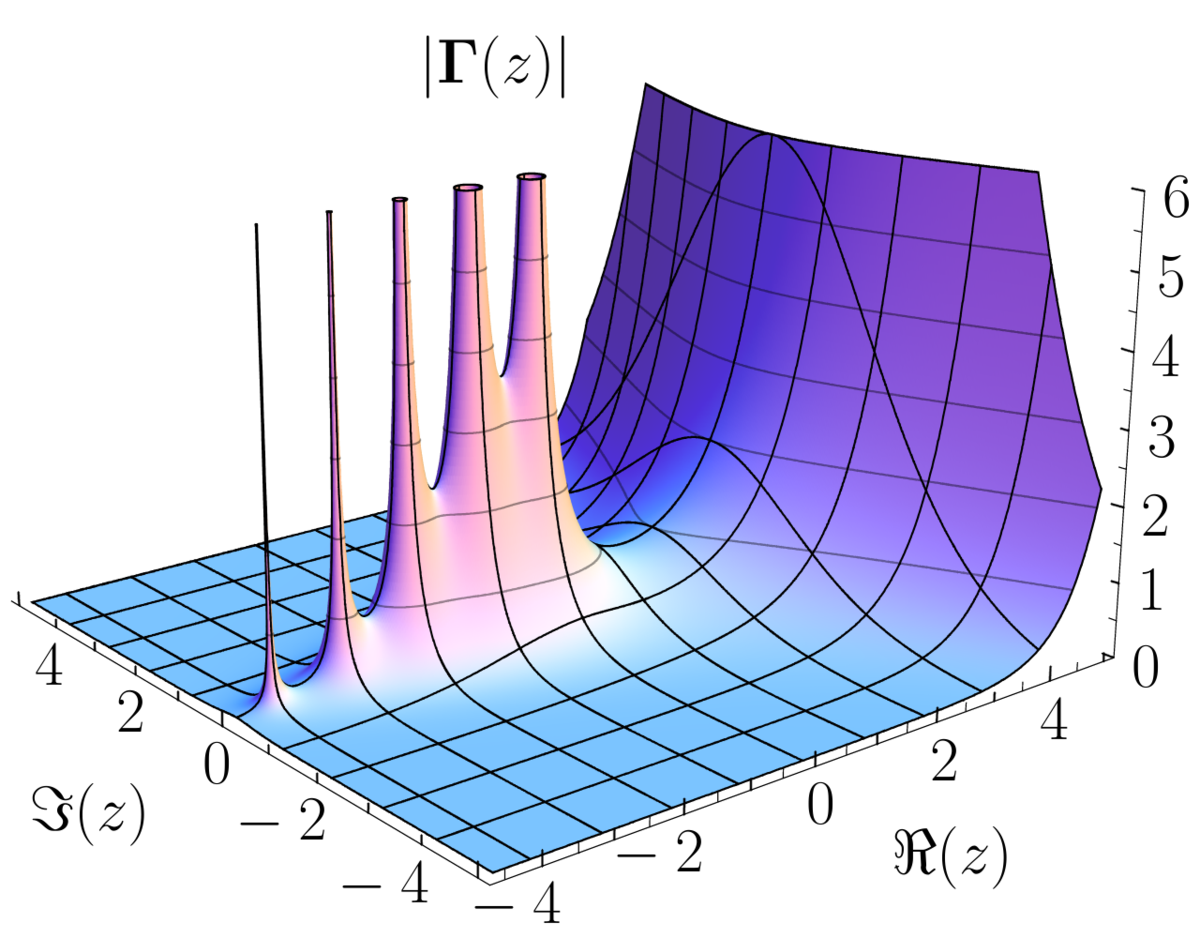

Presbuger Arithmetic

Another beautiful example of walking the tightrope of decidability is Presburger Arithmetic. Surprisingly, it is a formulation of arithmetic

where every statement is decidable by a simple algorithm. For example, you can say

x+y > 10 and the Presburger algorithm will find all satisfying x and y. What is the catch?

There is no multiplication. Presbuger Arithmetic only has plus, equals, there exists, and for all.

So statements about prime factorization, for example, are impossible to state in Presburger Arithmetic. It seems that multiplcation is intricately linked with undecidability. And

Once we say we want multiplication, arithmetic no longer becomes decidable.

Undecidability is Interesting

Unlike programmers, who would want decidabilty type systems, we mathematicians do not want decidability in our systems. In truth, decidable systems are boring, and pose no interesting mathematical questions. Due to the well-established relationship between expressiveness and decidability, once we make a system expressive enough to pose interesting questions, it becomes undecidable. Furthermore, in decidable systems, truth is simply a matter of computation. If you want to check if a statement is true, just run a computer to check it. Mathematics in decidable systems loses all its beauty and elegance of unconventional proofs. So maybe undeciability isn't so bad.

Walking off the Cliff

What can you take away from this? Well let's say you're designing a programming tool like a configuration language or a macro system. Users might demand more and more features, until, unwittingly, your simple little tool becomes undecidable. This happened to C++ templates, where now they are turing complete (or in other words undecidable). So my advice is to keep in mind the original goal of your project and be aware of any features that might cause you to wander from the island of safety that is decidability.